** When you buy products through the links on our site, we may earn a commission that supports NRA's mission to protect, preserve and defend the Second Amendment. **

Whether weaponlight, laser or combination thereof, the standard Picatinny rail will accomodate your accessory needs.

Polymer-frame pistols rule the military and law enforcement worlds and are clearly the most popular handguns among the concealed-carry set as well. As originally predicted, they provide a substantial savings in weight and price.

Some guns transcend their basic defined purpose and make the manufacturer famous in the process. Although it had a lot of help from a series of movies, the Walther PPK became such a weapon as the pistol carried by James Bond, the most famous secret agent of all time.

A fact not known by all movie goers, the Walther was also the first double-action pistol ever produced. Of lesser fame at the movies but even more respected by military personnel is the Walther P38, the first military-issued double-action pistol used in World War II. Even less well known is that Carl Walther and his son Fritz made the very first semi-automatic pistol in 1886. During World War I, the first production semi-auto handgun, Walther’s Model 1, was issued to and carried by almost all German officers. The company may be newly arrived in America, but it is definitely not new in the pistol business.

For those who prefer their support hand to wrap around the trigger guard, the PPQ M2 has molded grooves to assist in purchase.

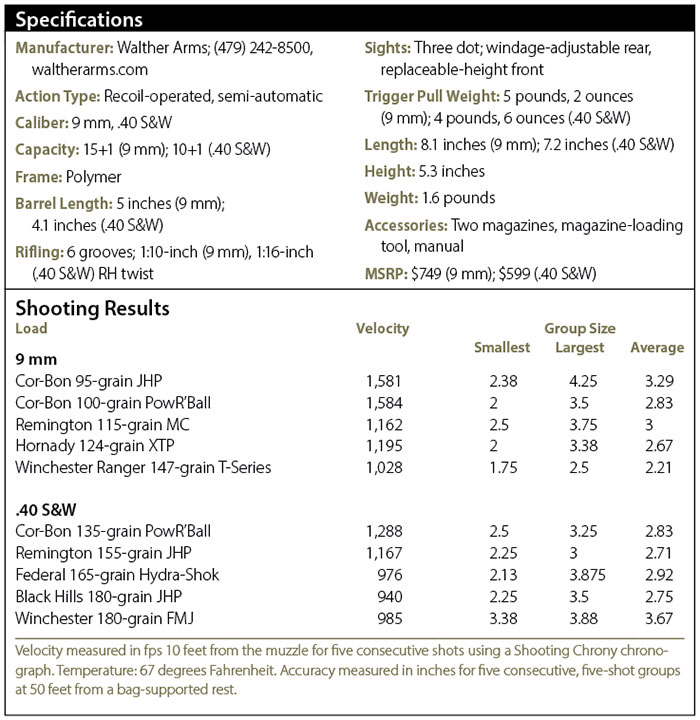

Recently, I’ve worked with a pair of PPQ M2 pistols from Walther Arms, one chambered in .40 S&W and the other in 9 mm. According to the included manual, PPQ stands for Police Pistol Quick. Don’t dwell on that name—after the manufacturing department builds a gun, marketing and sales guys get to write a script, and in the case of the PPQs, what they say is a pretty accurate and factual description of the gun’s attributes and capabilities. Like most of today’s duty pistols, the PPQs are recoil-operated, striker-fired semi-automatic pistols with a steel barrel and slide and a high-strength polymer frame.

Small, medium and large grip inserts ensure the PPQ grip can be custom-tailored to the individual shooter’s hands.

Extremely important in a fighting handgun, the PPQs can be fired with the magazines removed. If you lose or break a magazine—or get surprised in the middle of a tactical reload—you still have the round in the chamber to deal with the situation. The PPQs also came with a magazine-loading tool. If you’ve never been through several days of training with a double-stack-magazine pistol, you may not appreciate this little tool. Trust me, your thumbs will love you for using it.

Immediately noticeable on both guns is the accessory rail where you can mount a light or laser. On a duty gun or defensive pistol for home defense, I see no reason not to have a rail. It adds very little weight to the pistol, particularly on a polymer gun. And a light mounted on a handgun provides a huge advantage in a low-light encounter by allowing you to use your standard two-handed shooting grip. The actors in cop shows make it look simple to walk through a building with a light in the support hand held next to the gun, and it is, right up until you fire the first shot. After that, good luck keeping both gun and light trained on your assailant.

Taking ambidextrous controls to the next level, the PPQ M2 has both slide-stop and magazine-release levers on both sides of the pistol, making it easy to operate with either hand.

Three backstrap inserts of different sizes come with each gun. My short fingers prefer the smallest strap, and when it was installed, I was able to hit the magazine-release button with the thumb of my shooting hand without changing my grip—that’s something I can’t do reliably even with my beloved 1911s. The inserts are easily changed by removing a pin from a recess at the lower end of the backstrap. The recess and the pin can also serve as a lanyard loop if you’re so inclined. Just insert a lanyard when switching the straps, and you’ve got a convenient retention device.

The PPQs are available with either steel or polymer sights, both of which are replaceable. Both front and rear sights are adjustable. Windage adjustments are performed by drifting the rear steel sight left or right, while the plastic sight has a screw permitting click adjustments—specifically one click moving the impact point roughly .75 inch at 25 yards. For elevation changes, different height steel and plastic front-sight blades are available. The plastic sights on the tested guns were equipped with the standard three-white-dot system, and the rear notch on both samples seemed wider than on other pistols I’ve used. This wide notch facilitates faster acquisition of a flash sight picture, which is of course very desirable on a defensive pistol, but it doesn’t help precision shooting, at least for these aging eyes. For that reason, I opted to perform accuracy testing at 50 feet instead of 25 yards. What I really liked about the PPQ sights was the white-dot sight picture shot to the same point of impact as the conventional sight picture. That hasn’t been the case with other guns.

Simple, common takedown procedures reduce the PPQ to its components for cleaning and lubrication.

Overall, I like the ergonomics of the PPQ. There are edges where you need them, like the serrations on the slide, the slide-stop levers and the accessory rail, but even these are not aggressively sharp. Grips and backstraps have a rough texture to facilitate control of the gun during rapid fire, but the texture is not so rough to chew your hands up. The pistol felt comfortable in my hands and pointed naturally wherever I looked.

Viewed from the rear, the slide has a trapezoidal shape with the sides sloping in toward the top. I prefer parallel sides on a pistol with heavy recoil springs, because it’s easier to manually cycle the slide. My hands tend to slip off the slide toward the narrower dimension, in this case the top of the slide. Occasional minor bouts of arthritis make me a bit fussier about this shape than most shooters, but even for me it’s really not a big deal, although I found the slide shape slightly more aggravating on the .40 S&W than on the 9 mm.

The forward serrations on the Walthers help greatly in maintaining a grip during a chamber check. The trigger guard is slightly relieved where it joins the frame to assist getting your shooting hand as high into the gun as possible and minimizing shot-to-shot recovery time. While recoil is not a major factor on the 9 mm, the sharper recoil impulse of the .40 S&W—particularly in a lightweight polymer handgun—is where this feature will be most appreciated.

I’m not at all ambivalent about the forward hook of the trigger guard—I just don’t like it. Since I don’t shoot with my support hand in front of the trigger guard, I see no need for it.

Takedown procedures for the PPQs are pretty simple, just be very careful not to put any part of either hand in front of the muzzle. Make sure the pistol is empty before disassembly.

“PPQ” is shorthand for Police Pistol Quick, which the handgun proved to be in testing.

When you decide to fire that first shot, you’ll really begin to appreciate the PPQ. After the trigger slack is taken up (which requires about .2 inches of trigger travel), the 9 mm required just more than 5 pounds of pressure to fire, while the .40 S&W required less than a 4.5-pound pull. The triggers on both guns moved another .4 inches while that pressure was applied for a total travel distance of .6 inches.

But it’s when you fire the rest of the rounds in the magazine that the real love affair starts with these Walthers. The triggers on both pistols reset with less than .2 inches of forward travel, so on subsequent shots, the trigger moves less than .2 inches, while requiring the original 5 pounds or less pressure to fire. If you’re a trigger slapper, you’ll be back to the long trigger pull of .6 inches experienced on the first shot. The good news is each shot will still require only 5 pounds pressure.

Mastering the short, trigger reset technique is difficult enough on a square range when fighting paper targets. It gets even tougher when you go through a shoot house. In a real-life scenario where live rounds might be coming at you, your sphincter will be fluttering like a hummingbird and your trigger-slap technique will return with a vengeance. Unless you’re a highly trained ninja, life-threatening situations like a gunfight tend to produce panic and restore bad habits.

Walther’s manual says the PPQs can handle +P loads, but such loads will accelerate wear and dictate more frequent maintenance. The manual also says that +P+ ammunition should not be used, and the guns should be cleaned prior to their first firing. I heeded the instructions regarding ammo, but ignored the initial cleaning. In the first four magazines I put through the pistols, there were two failures to extract. After that, things settled down and there were no further malfunctions with either +P or standard-pressure ammunition during testing. I score that as two failures for the gunwriter, zero failures for the PPQs.

I mentioned that I performed testing at 50 feet rather than 25 yards because the wide rear sights seemed to be made for quick acquisition rather than precision shooting. Perhaps that’s why the word “quick” is included in the PPQ name. I used the leftover ammo in a 50 yard duel with an 8-inch falling-plate target. Seated in the same armrest position as used in the group testing, the plates were hit with 30 to 40 percent of the shots. Precision repeatability with the Walthers may be beyond my visual capability, but the guns are capable of longer-range shots should such be warranted.

Fast at close range and capable of decisive hits at longer ranges, the Walther PPQ is a well-built handgun. Include these capabilities in a lightweight, easy-to-shoot pistol, and you have a self-defense sidearm worthy of serious consideration.