It’s not often that I get really excited over the launch of a new handgun. This goes back long before my professional-reviewer days that started more than a decade ago. As far back as the late 1990s, I’ve been throwing shade at supposed “totally new directions” launched by various manufacturers.

Sometimes this involves not getting ecstatic at the latest offerings from established makers. The SIG Sauer P320/P365 are solid guns, but c’mon man, everybody and their brother is riffing on the striker-fired, polymer-popper game these days. The P250 was at least a novel new creation when it came out.

Similarly. Kimber’s K6 revolver didn’t get me overly excited. OK, cool, it was a new revolver from a company not known for revolver manufacturing but—well, I don’t want to sound like a fuddy-duddy, but the truth is the whole medium-frame-revolver concept was pretty much solved way back when Smith & Wesson launched the Model 13.

Enter the Glock spinoffs.

Allow me to explain: Most Glock generations after the Gen3 have an ulterior reason for existing, and that’s introducing new and patentable features and mechanisms, be- cause the Gen1 through Gen3 are all essentially open source now. The Gen3 guns remain popular to the point that they remain in production at Glock largely to fulfill remaining legacy contracts.

This popularity, and the open-source nature, means that there are numerous manufacturers offering what are essentially Gen3 Glock G19 and G17 clones of varying degrees of fidelity to the original and quality of execution. I haven’t paid much attention to most of these because, well, yawn, amirite? If you want a cheap Gen3 Glock G19, the used showcase at your local gun store has plenty to offer, so no need to go looking at an off-brand clone unless you just gotta have a new pistol.

Then came the RXM from the team of Ruger and Magpul. A Gen3 clone, maybe, but something was gained in translation.

On its surface, this is yet another pistol I shouldn’t be excited about at all, and yet I was only about two magazines into the first range session with the test gun before deciding that I was pretty stoked about it and had decided to buy the writer’s sample. I suppose that now I must explain to you, the reader, why I had that reaction.

In a nutshell, it’s because all the Third Generation Glock G19 clones on the market up until now have largely been exactly that: clones. The RXM is different, however. It is an actual product-improved Gen3 Glock G19; it is better than the original.

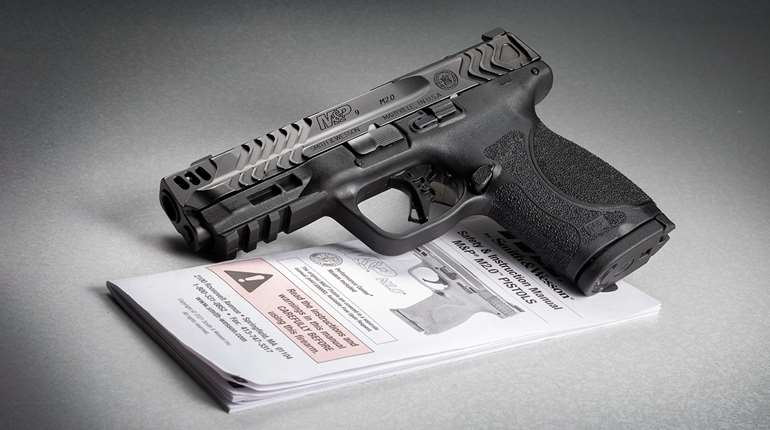

In its overall dimensions, this is another G19 copycat. It’s a pistol with a 4-inch barrel and a compact grip length just long enough to accommodate a 15-round magazine of 9 mm ammunition.

At a glance, the slide has the familiar, boxy silhouette of the Austrian polymer-frame handgun. While it has the same beveled snout to let the pistol find its way more easily into a holster, there are other differences, both cosmetic and functional.

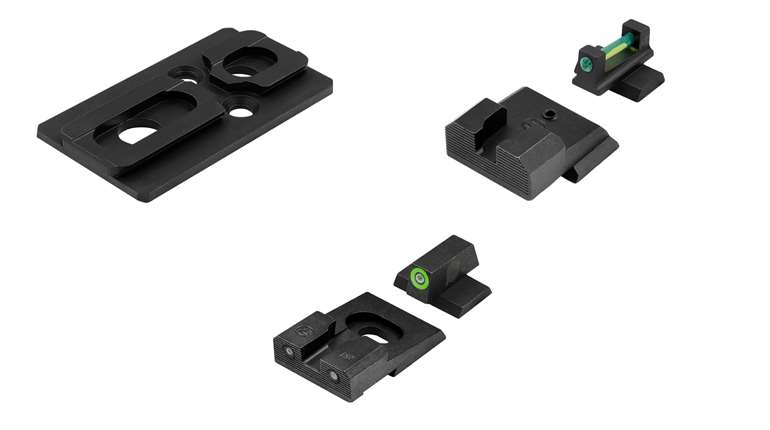

The top of the slide is flat, with the front and rear sights mounted via the normal Glock-compatible dovetail in the rear and threaded tenon up front. The bevels to either side of the flattop are slightly more pronounced than on the Austrian original, and the rear edge of the barrel hood has a notch cut for use as a loaded-chamber indicator, a needed feature that consumers have increasingly come to expect. Aft of the ejection port, you’ll find—well, we’ll get back to that.

In addition to the cutout in the chamber hood, the external extractor has a bump on it that protrudes noticeably when a cartridge rim is under the claw, serving as an additional visual and tactile loaded-chamber indicator. There are five pairs of slanted grasping grooves located at both the front and rear end of the slide, allowing for a variety of manipulation styles. Rather than the flat sides of a Glock, the forward end of the slide has a sort of stair-stepped contour reminiscent of a SIG Sauer product.

Moving down onto the frame is where the Magpul influence on the project becomes readily apparent. It’s a matte gray (Ruger calls it “Stealth Gray”) polymer. At the time of this writing, Ruger and Magpul both also sell grip frame modules in black, flat dark earth and OD green.

Up front on the frame’s dustcover is an accessory rail with a single notch out by the snout. Rather than masquerading that there is some wide variety of weapon-mounted lights waiting to be attached to this mid-size pistol, Ruger and Magpul have set their pistol’s frame up for X300/TLR1-size lights, and that’s how it will be.

The matte, polymer frame has coarse texturing on the frontstrap, backstrap and both sides of the grip, as well as small pads above the trigger guard on both sides. Unlike the third-generation Glock from which it is derived, the frontstrap is devoid of finger grooves. Similarly, the backstrap exhibits a complete absence of an arch, being totally straight. Considering that companies like Boresight Solutions and Bowie Tactical Concepts have sprung up over the last several decades based on removing the finger grooves and backstrap arch from Gen3 Glocks, this is obviously a market looking to be filled.

If you are a southpaw, by which we mean that God put your right hand on the wrong side, the Ruger RXM is going to make you party like it’s 1999. This is, after all, more or less a Gen3 Glock clone, so features like ambidextrous slide stops and reversible magazine releases are not a thing here. (As a natural left-hander obliged to shoot right-handed, whenever I use a pistol with ambi controls, I wind up using the right-hand controls with my trigger finger, which works well here.)

Sliding down to the bottom of the grip frame, the mag well opening is noticeably flared. There’s no lanyard hole on the backstrap to enable easy installation of an aftermarket mag well, but neither is there a need for one. The RXM ships with two 15-round, Glock G19-compatible magazines, and you can practically toss them in from across the room. Out of curiosity, I tested the sample pistol with the provided Magpul mags, as well as factory Glock magazines, ETS mags and the aftermarket Magpul 9 mm Glock magazines I had on hand, and all of them worked fine.

The trigger has a tabbed trigger shoe and—here’s the thing that really made me fall in love on the first range trip—the trigger on my test gun broke consistently at 4.5 pounds with a very predictable rolling break. Out of the box a “Practical/Tactical” longslide Glock model tends to have a trigger closer to 5-plus pounds than the touted 3.5. The RXM trigger is as good as any Gen5 Glock I’ve tried.

Fieldstripping the Ruger RXM is just like any Gen3 Glock: Clear the pistol, triple check that it is clear, dry-fire in a safe direction, slightly retract the slide, pull down on the takedown levers on the frame, and let the slide forward off the frame. After this is done, one can discover one of the two big differences between the RXM and the Gen3 Glock.

Fieldstripping the Ruger RXM is just like any Gen3 Glock: Clear the pistol, triple check that it is clear, dry-fire in a safe direction, slightly retract the slide, pull down on the takedown levers on the frame, and let the slide forward off the frame. After this is done, one can discover one of the two big differences between the RXM and the Gen3 Glock.

Unlike the original, a polymer pin can be pressed out of the RXM frame and the whole chassis—which houses the trigger group and frame rails as well as being rollmarked with the serial number—can be lifted from the frame. Even with these differences, almost all mechanicals are interchangeable between the RXM and the third-generation Glocks.

Sliding back up to the top of the slide, we circle back around to the other big difference between the RXM and its Austrian forebear. Unlike the classic Glock MOS pistols which were, admittedly, pioneers in the factory optics-ready handgun market, the Ruger RXM does not use an adaptor-plate mounting system. The problem with adaptor-plate systems is that the adaptor-plate screws to the slide and then the optic screws to the adaptor plate. Once the optic’s mounted, you can’t see or adjust the screws mounting the plate to the gun, and there are a distressing number of incidents where the whole assembly departs the slide under recoil.

The RXM uses a system similar to the Springfield Armory Echelon, in that the slide is cut for an optic and has an array of holes and ships with locator pins to fill them that allows the pistol to direct-mount an optic that uses either the Trijicon RMR, Leupold DeltaPoint Pro or Shield RMSc/Holosun 507k footprints. These are rapidly becoming the standard MRDS footprints, and it’s good to see handgun manufacturers acknowledge this. I did my testing with a Trijicon SRO mounted on the test pistol.

Over the course of 600 rounds of assorted FMJ and hollow-point ammunition, the RXM did not experience any malfunctions, despite no maintenance beyond a healthy dollop of Lucas Oil added to the frame rails before the first range session. Accuracy was respectable, too, with several sub-2-inch groups fired at 15 yards while shooting from a casual rest on a range bag. A Gen5 Glock with its Marksman barrel is marginally more accurate, but the difference between the two is akin to picking fly droppings out of pepper.

Between the optics-mounting system and the true chassis setup in the frame, backed by the design knowledge of Ruger and Magpul, this is a pistol that is not just another Gen3 Glock clone, but is actually a better handgun than the Gen3. At this point, with all its added virtues, the only real question is “Does it hold up to high-five-digit round counts like the original Glock?”

Well, that’s the next thing yours truly aims to find out.