Prehistoric records may be unavailable, but you can imagine what armed conflict must have been like among earliest humans. We know three things that had to be present at this primordial event: human aggression, extreme violence and the resulting carnage.

Although closed fists, knees, elbows, shins, forearms and headbutts serve as rudimentary impact weapons, it probably didn’t take the first hominids very long to discover that a hand-held weapon such as a rock or a tree branch yielded greater results.

Modern Era

Over millennia, impact weapons such as the war hammer, flail and mace were continually refined. In Western Europe, the club, staff and walking sticks—such as the French cane, English quarterstaff and Irish shillelagh—are but a few extant examples. Akin to their European counterparts are the South African Knobkerrie, the Nguni and the Zulu Izinduku.

Impact weapons were concurrently devel-oped in Asia, such as the Chinese three-section staff, nunchaku and short staff, which are akin to the Japanese Bo, Bokken, Jo and the Okinawan Tonfa.

Commensurate with the global development of the impact weapon is their tremendously effective usage in mortal combat. European fighting systems originating from the pre-Greco-Roman era morphed into independent systems such as the quarterstaff popular in 16th century English and German stick-fighting schools, to include the French La Canne system and others.

Some impact-weapon fighting systems date back to antiquity and can be viewed in their contemporary martial arts forms such as Lathi from India, Bando from Burma (Myanmar), Seng Gigi from Lombok (Indonesia) and Nguni (Donga) from Africa. The Wushu and Shaolin fighting systems of China, Kendo of Japan and Kali, Escrima and Arnis from the Philippines rank among the many impact-weapon-fighting arts taught to this very day.

Brutally Effective

Speaking of the Filipino Martial Arts, a significant number of Filipinos migrated at the end of World War II to Stockton, CA. Among them were stick-fighting masters (called Guros), who brought with them their ancient and secretive impact- (and edged-) weapon arts.

To preserve their ancient practices, the most prominent of these masters passed their mysterious fighting arts on to the next generation of Filipinos living at that time and in that area. Guro Dan Inosanto is one of the select few who grew up and trained among the masters and grandmasters of Kali, Escrima and Arnis in and around the migrant farming communities of Stockton.

Today, Guro Inosanto is the recognized conservator of at least 28 different Filipino martial-arts systems. Extremely highly trained, knowledgeable and skilled, Guro Inosanto also happens to be the longest-term (13 years) training partner of martial arts legend Bruce Lee and co-starred in his movies demonstrating the nunchaku and kali fighting sticks for the very first time to world-wide audiences.

Stick fighting is as brutal and deadly as it is beautiful to watch. Back in the day, were you to face-off with a highly trained practitioner, the price of failure was death.

When I wore a younger man’s clothes, I was very fortunate to have studied in Stockton, CA, with one of Guro Inosanto’s instructors, U.S. Army World War II veteran and Grandmaster Leovigildo Miguel Giron. Later in my training, I was introduced to and began my training as a disciple under Guro Inosanto (also a U.S. Army veteran) and Punong Guro Edgar Sulite in the traditional Filipino martial arts.

It was standard fare for my training partners and I to spar and compete in full-contact stick tournaments, as well as backyard unofficial “contests of skill,” with impact weapons. Knowing what it’s like to both strike and be struck by another highly trained stick fighter, I can tell you this: it’s no joke, and it can cause substantial bodily harm. No one dares fight without a helmet or some type of head protection these days, because we all know that a highly skilled stick fighter can put your lights out with a single, well-placed strike.

Impact weapons are utilized outside the realm of martial arts, with practical application in the civilian, military and law enforcement realms in the form of fixed batons, expandable batons or PR24s (Tonfa). As such, certain impact weapons are often carried on duty.

Stick fighters use fire-hardened rattan with both ends cut completely flat. Law enforcement uses everything from hardwoods to high-impact-resistant resins to tempered steel and aircraft-grade aluminum. Regardless of construction, like any other tool it’s not the weapon itself, but the person wielding it, that makes it a formidable self-defense tool.

Given our contemporary world of weapons ranging from laser-guided missiles to handguns, impact weapons fall under the category of “non-ballistic.” Unlike with a firearm, impact-weapon combatants must be up close and personal—within arm’s reach of the other to facilitate an effective strike or defense.

Impact weapons possess a multi-faceted array of core-combat capabilities such as striking, immobilization (locks), takedowns, choke-outs, throwing and even breaking the human neck. In my opinion, they are the most effective of non-ballistic weapons. When asked if I prefer either a stick or a knife in self-defense against a knife attack, my response is immediate—the stick is a far superior tool due to its crushing impact power, superior range and rapid deployment.

Weapon of Opportunity

Aside from a police baton or a martial-arts fighting stick, there is an unlimited selection of improvised impact weapons out there that can be used as a tool of opportunity in the event you may need to defend yourself in a life-or-death, real-world threat engagement.

If you know what you’re looking for, you can find impact weapons anywhere you go. If indoors and snooping around a garage, utility closet, trunk or backseat of your car—or even leaning up against a nearby wall—you may find the likes of a broomstick, plunger, rolling pin (in the kitchen), walking stick, umbrella, shovel, golf club, crowbar or baseball bat. Roaming around outdoors, you may stumble across a hand-size rock, a perfectly shaped tree branch which may be used as a club or a walking stick, a piece of discarded pipe, a chunk of wood, a brick or angle iron.

Some impact weapons are legal to take inside places that may forbid the carry of firearms, knives or other self-defense tools. The likes of walking sticks, canes, crutches and other medical devices cannot be denied access to you in many such environments, and they can be formidable weapons in the hands of a skilled practitioner.

Skill Building

Learning how to fight with an impact weapon is like learning how to shoot. For self-defense, like a gun, an impact weapon must be readily accessible. It can be carried on your body, or at least within arm’s reach. You first need to know how to achieve a positive grip on the tool. The impact weapon of choice or necessity can be deployed with either your strong (dominant) or support (non-dominant) hand, or even with two hands if it’s hefty enough. With adequate length, it can be used like a baseball bat.

If used as a weapon of opportunity in self-defense, you must first learn how to block incoming strikes and know what parts of your body to protect and why. Like any martial art, it takes many years of about 30-plus hours a week to put the kind of time necessary to gain master-level skills. Since most of us don’t have that kind of time, we can at least become familiar with some of the basics.

Consider if you had to take someone who knows nothing about your job (or career) and you had to teach them everything you know in one day. What would you teach them? Probably the very basics.

If you are a heart surgeon, you certainly couldn’t pass on much more than a first-aid class to include how to use a tourniquet, plug a sucking-chest wound and maybe CPR. The same applies to knowledge of using an impact weapon in self-defense. Let’s start with the basics.

Self-Defense Basics

If someone was attacking you with a machete, hammer, axe or other hand-held, non-ballistic weapon and was intent on smacking you in the melon, you’d need to protect from your collar bone and up. Why the collar bone? Because it’s where the neck starts. The neck is considered a conduit of the various systems that support the computer (your brain).

The conduit allows for hydraulics (circulatory system via the heart and major arteries), pneumatics (oxygen flow from the lungs) and electronic messages from the computer down the brain stem to your body. So, the computer and its conduit are pretty darn important parts to protect.

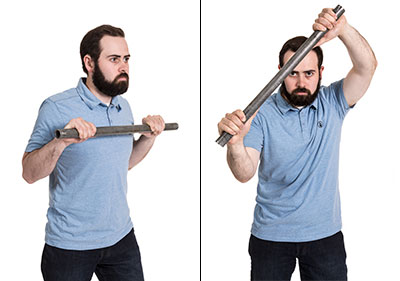

With a sturdy enough impact weapon, you can hold it with both hands (recommended). To find your optimal defensive grip, let the object hang loose in your hands with both palms down and your thumbs lightly touching your quadriceps. Raising the object up, parallel to the earth, you can protect your conduit.

As you continue to move the weapon upward, stay connected with both hands and move one hand above the other to place the weapon at a 45-degree angle, with the higher hand being above your head. This forms the shape of a roof angle. Like rain or hail hitting a roof, you want any incoming strike to deflect away from your computer. It’s never a good idea to hold the weapon square over your head, because the energy has nowhere to dissipate except through it and then onto your brain box.

The two-key teach points of this defensive maneuver are that you must position yourself so that you can see the threat from under the weapon (your eyes must be under the roof) and that the weapon is angled 45 degrees (to facilitate incoming-strike deflection).

Following your block of the incoming strike, you then need to immediately move your body to the left or right, trying to move behind your opponent. Your body movement makes him respond to you, rather than you responding to him or her. While you’re in motion, you can use this valuable fraction of a second to prepare for what may be your one and only opportunity to stop the threat with an impact-weapon strike.

The most-common impact-weapon strikes are the baseball-bat strike (if you have enough space) or the two-handed strike to the trachea using the middle of the stick (if you are extremely close and have no time or space to move). Unlike ballistic weapons, which are powered by combustion, impact weapons require generation of force via body mechanics, transfer of kinetic energy and the controlled placement of both.

To create optimal impact, you need to create at least two intersecting force vectors. Imagine a car travelling at 50 mph smashing into a parked car, versus a car travelling at 50 mph in a head-on collision with another car also travelling at 50 mph. You want to generate maximum linear force created by your body. The martial concept here is to “attack the attack.”

Generate two force vectors and apply them to the intended target area. The first force vector is the centrifugal force generated by your arms—the swing, like a baseball batter or a golf swing. Do not stop short. Go all the way through, with what is commonly referred to as follow-through on that swing.

The second force vector is the linear or kinetic force of your body moving toward the target area by stepping forward with your lead foot. Combining both force vectors (centrifugal and linear) and placing them on a single point on your target, you have maximized the usage of your impact weapon as an effective self-defense tool.

Where to find Training

You can find impact-weapon training at various seminars and workshops offered around the country, usually at a martial-arts school that offers training with impact weapons such as a Filipino Martial Arts.

One of my most-popular seminar classes is the “Defensive Walking Stick,” which is taught at various locations. If unable to attend a professional workshop, there are many Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) schools around the country, which can be found in or near most major cities. Each has a traditional stick- and knife-fighting curriculum. You can also search the omniscient internet for DIY training videos and other online instruction.

In my humble opinion, there are only two types of people in the world of self-defense: those who are trained and those who are not trained. Improvised impact weapons as self-defense tools of opportunity can be found anywhere and everywhere. Like learning first-aid to stop the bleeding or how to use a fire extinguisher to stop a fire, you only need to be proficient enough with a handful of basic skills to use an impact weapon to stop a threat in self-defense.