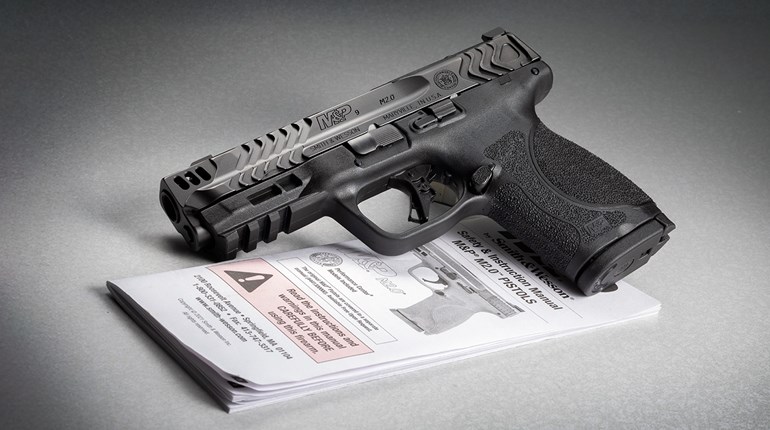

In 2025, armed citizens enjoy a broader variety of defensive-handgun choices than ever before. In terms of guns commonly available at your local gun counter, off-the-shelf handgun accuracy and reliability is as high as it has ever been. It’s a wonderful development that firearms manufacturers are producing such a broad array of makes and models that function reliably, but this has led to neglect of foundational gun-handling skill in the average person’s practice routine: malfunction drills. Despite production handguns being more reliable than ever, I believe occasionally practicing malfunction drills remains an important part of a quality practice routine and can build life-saving skills if we ever have to use our handguns to protect our loved ones or ourselves.

“But My Pistol Never Malfunctions!”

It’s a great thing to have a reliable carry gun, and one that has been shot regularly for years without a single malfunction gives us great peace of mind. However, presuming that because something has never happened before it will not happen in the future has a name: Normalcy bias. There’s a first time for everything, and the possibility of a malfunction in the future is always there. Hopefully the malfunction we encounter unexpectedly is during routine range time or at worst during a competitive match.

We’ve all probably been at the range or in a shooting class and seen someone experience a malfunction while shooting a drill or a course of fire. If they haven’t learned how to clear malfunctions and practice enough to do it without much deliberation, they often freeze and just stare at the gun like a primate staring at a wristwatch. The worst case is a having a malfunction during a real-world defensive gun use, and if we haven’t practiced enough to know what to do and do it quickly and correctly without thinking, then the cost might be astronomical.

So why am I even concerned with malfunctions if they’re so rare with modern production handguns? There are two primary reasons. The first is that as with any complex machine, parts wear, lubrication dries up, springs weaken and eventually the machine will fail to do what we ask it to do. You can certainly mitigate this with routine lubrication, rotating and maintaining magazines, choosing quality ammunition and other things. Ultimately, though, malfunctions are generally inevitable, even if you’ve not experienced one yet.

The second reason is a big one. Semi-automatic handguns operate based on the cycling of the slide all the way to the rear and all the way forward. Modern semi-autos function incredibly when held in a solid two-handed grip providing the necessary stable platform for the recoil cycle to occur, ejecting the spent casing and loading the next round in the chamber. If we see malfunctions on the flat range, a newer shooter failing to grip the gun hard enough and inducing malfunctions by limp-wristing the gun is often the cause, and a solid grip will solve the issue. This really becomes apparent in shooting classes when a group of shooters practice one-handed shooting, especially with dirty guns that need lubrication. The surest way to induce a malfunction in even a quality semiautomatic pistol is to shoot it with a suboptimal grip, or from an unorthodox angle or compromised shooting position where you don’t have an ideal grip on the gun, or to impede the slide with a foreign object like your clothing or a part of your hand because of a subpar grip.

It just so happens that in chaotic, messy, real-world defensive gun uses, sub-optimal grips, compromised and unorthodoxy firing positions and foreign objects getting tangled up with your gun are far more common than they are on the flat range. Subcompact semi-automatics are also more sensitive to limp-wristing, sub-optimal grip, unorthodox shooting positions, or slide impediments than larger handguns. Guess what type of handgun is more popular for concealed carry? You guessed it: compact and subcompact semi-automatics.

So even if you’ve never experienced a malfunction with your carry gun on the flat range shooting it from a solid stance and two-handed grip on the range, if you ever find yourself flat on your back between two cars in a parking lot trying to hang on to your attacker’s arm that’s holding a knife or a crowbar and access your gun to save your life, the odds you’ll have a less than perfect grip or that your (or their) clothing gets tangled up in the slide go way, way up. Rather than learn how to clear malfunctions in the moment, it would probably be smart to practice occasionally so you’ll have the muscle memory if you ever need it in an emergency.

Two Steps to Success: “Tap, Roll, Rack” and “Drop, Rack, Load”

Two Steps to Success: “Tap, Roll, Rack” and “Drop, Rack, Load”

There is a myriad of ways that malfunction clearance is taught, but I use a simplified method. Instead of categorizing the different types of malfunctions and creating a bunch of decisions you have to make based on whether it’s “Type 1,” “Type 2,” etc., I just teach a two-step process that will fix every fixable malfunction you are likely to encounter while shooting.

If you’re shooting a gun and it stops shooting, you may just be out of ammo and it’s time to reload. If so, reload. If you know there are still rounds in the magazine and realize you have a malfunction, bring the gun back slightly towards your torso keeping the muzzle flat and toward whatever you were shooting at, so you can more easily manipulate the gun closer to your body, and follow three steps:

1.) Firmly tap the base of the magazine to ensure it is fully seated.

2.) Roll the handgun to the right (ejection port side).

3.) Rack the slide firmly to the rear allowing any spend casings or obstructions to fall free of the ejection port and release the slide vigorously. If this successfully clears the malfunction, reassess whether you need to continue shooting and shoot if needed.

If “Tap, Roll, Rack” does not successfully resolve the malfunction, we don’t waste time repeating a step that doesn’t work and instead will move on to the second solution: “Drop, Rack, Load.”

If you perform “Tap, Roll, Rack” and it doesn’t work:

1.) Press the magazine release and drop the magazine. If you carry a spare magazine then you can allow the magazine in the gun to fall to the ground, but if you do not carry a spare magazine, you need to retain it by either sticking it in a pocket or tucking it in your armpit, pinching it in between your firing hand pinky finger and the grip of the gun, or dropping it a couple inches within the magazine well and holding it there with your pinky finger if your hands are large enough.

2.) Rack the slide firmly and vigorously to extract any casings. It may be necessary and prudent to rack it multiple times if you have a casing stuck in the chamber that is failing to extract.

3.) Once the gun is completely empty and all obstructions or malfunctions are cleared, load the gun and reassess whether you need to continue shooting.

“Tap, Roll, Rack” will typically fix the common failure-to-feed and stovepipe malfunctions. “Drop, Rack, Load” will typically fix the dreaded “failure-to-extract” or the “double feed.”. If neither of these remedies work, you may have a serious issue like a broken extractor and need to draw this conclusion: Your gun is broken and inoperable, and however you solve the problem you’re facing, your gun isn’t going to be part of the solution unless it’s as a blunt object.

Practice Routine

Practice Routine

How do we practice these skills? Practicing “Tap, Roll, Rack” at the range is incredibly simple. To do it at no additional cost, you can randomly load three to four of your spent casings in your magazine mixed with live rounds (Don’t put two spend casings in the magazine consecutively). When you press the trigger and nothing happens, go through the “Tap, Roll, Rack” procedure and then reassess and resume shooting. You can also purchase and use dummy rounds instead of spent casings for your caliber of handgun at a very modest cost.

For practicing “Drop, Rack, Load” you can lock your slide to the rear, manually place a spent casing or dummy round in the chamber. Never use a live round in the chamber – the nose of the round in the magazine (If a live FMJ) can hit the primer of a live round in the chamber and cause an out of battery detonation. Then load your magazine and ride the slide forward inducing the malfunction. Go through the “Drop, Rack, Load” procedure, reassess whether you need to shoot and act accordingly, and then set it up again.

You can also do both malfunction clearance procedures entirely with dummy ammo as part of your dry fire routine. If you incorporate these procedures into your routine dry practice and live practice, when your gun malfunctions on the range, during competition, or in the street, you’ll be able to clear it quickly and correctly and get back to solving the main problem at hand.