Checking headspace is as simple as buying GO and NO-GO gauge sets in order to ensure your rifle will function safely.

The hottest new cartridge has just hit the street. You want to add an upper to your existing AR in order to take advantage of this new thumper’s impressive external ballistics. Gunwriters, bloggers, ammo companies and the guy who dominates your local gun store all say that because you can use your existing 5.56 NATO bolt-carrier group (BCG) in the new upper, this conversion is a no-brainer—and they have a point. After all, using one BCG for multiple uppers is a good way to save money and streamline your logistics. In fact, several popular cartridges share common bolt face and extractor-groove dimensions. Some examples are 5.56 NATO with 22 Nosler, .300 BLK or .350 Legend; 6.8 SPC with 224 Valkyrie and .308 Win. with .243 Win., 6.5 Creedmoor or 7 mm-08 Rem. Unfortunately, the experts neglected to tell you that just because your old bolt will function in the new upper doesn’t necessarily mean the two should play in the same sandbox. For some reason, a little detail called “headspace” tends to get left out of this equation. That’s regrettable, because a bolt and barrel that are not properly headspaced can fail in a way that may cost you many times more money than the amount saved by not also buying a new bolt.

According to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, Inc. (SAAMI), headspace is “The distance from the face of the closed breech of a firearm to the surface in the chamber on which the cartridge case seats.” The location of that chamber surface differs by case type. For example, bottleneck, rimless cartridges generally headspace from the mid-point of the shoulder to the bolt’s face, but rimmed, belted and straight-walled, rimless cartridges all use different index points. If there is a gap between that face and the case head—excessive headspace—you can have dropped primers, light strikes, case-head separation or split case necks. The term “catastrophic case failure” was not chosen arbitrarily to describe the worst-case scenario for excessive headspace.

Too little headspace also comes with potential hazards, such as failure to fully seat a cartridge and of the bolt to go completely into battery. Or, in the case of a primer that is not fully seated in its pocket, insufficient headspace may lead to a slam-fire. Further, if a shooter muscles such a bolt closed through brute force (never a good idea), the case mouth can be forced into the tighter bore leade, crimping it on the projectile and resulting in amped-up pressures. If the barrel’s throat is particularly short, it may also drive the projectile rearward into the case, compressing the powder charge to a dangerous level.

A couple myths about headspace seem to persist. The first is if the bolt closes on a factory cartridge, headspace is fine. The second is if a bolt headspaces in one barrel, it will headspace in another. Regardless of the sources and motivations for these fallacies, they are wrong. While it is true that more often than not, a bolt made to work with a specific barrel will headspace properly, it is not a guarantee. Whether you are dealing with the 24,000 psi of a .22 LR or the 63,000 psi of a .243 Win., if a cartridge fires in your rifle’s chamber while the bolt is partially out of battery, the potential for a face grenade exists. Depending on the severity, the event could simply leave you to pick a few brass flecks out of your cheek or it could result in a law enforcement officer standing at your front door, grimly explaining to your family why you will not be home for dinner. Suddenly, the advantages of a new cartridge that doesn’t need its own bolt don’t sound so great.

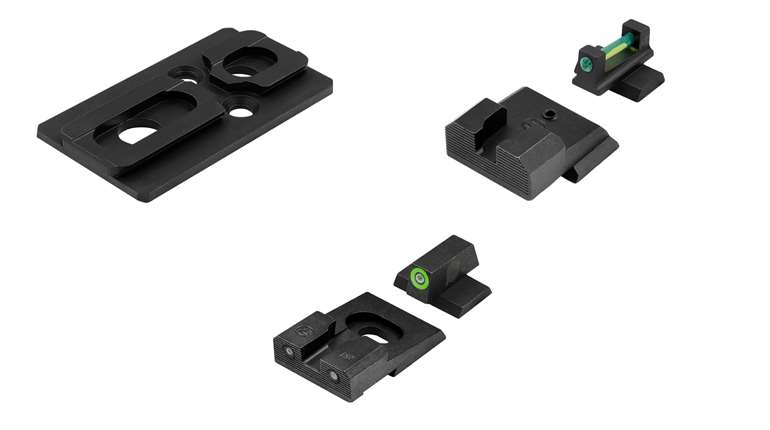

Fortunately, checking headspace is not particularly difficult. The process differs by firearm type, so if this is something you are not comfortable doing, enlist the services of a gunsmith. DIY-ers can buy “GO” and “NO-GO” gauge sets for $60 to $70. Some military chamberings also have a “FIELD” gauge, which is good to have, if available. Ideally, your stripped bolt will easily close when the GO gauge is inserted into the chamber, but not when the NO-GO gauge is in place. The gauge manufacturer’s instructions will explain how to perform this simple check, but it is important to follow them precisely. Here are a few additional pointers:

• Only use gauges from a reputable maker, such as Manson, Clymer or Forster.

• Never mix and match GO and NO-GO gauges from different makers in the same caliber.

• Never force a bolt to close on a headspace gauge. Doing so can provide a false reading, damage your bolt, receiver, barrel or gauge.

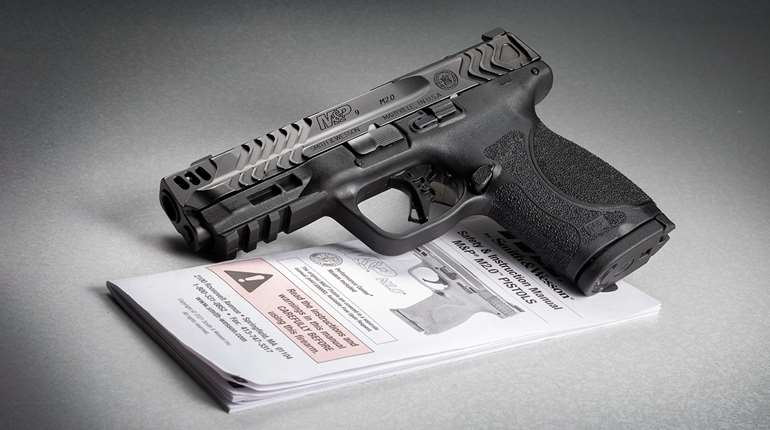

If you find that your new barrel and bolt combination fails a headspace check, the remedies will vary by firearm type. While bolt-action rifle headspace is usually adjustable (with proper tooling), a new MSR’s upper-receiver assembly will need a different bolt that passes the headspace test before it is safe to fire. The problem with just buying a new bolt is that there is no guarantee it will pass the gauge test. In my work as both a manufacturer and repairer of firearms, I sometimes go through several bolts to find one that headspaces properly. Regardless of rifle type, a gunsmith is most likely going to have the parts and tooling required to get you up and running quickly and safely.

In theory, bolts, receivers and barrels should all be made to common specifications for each cartridge. Life would be simpler if that were true, but the reality of different manufacturing methods, machinery and tolerances compels us to work within a range of minimum and maximum dimensions. If possible, purchase an already- headspaced bolt with any new, drop-in barrel or upper-receiver assembly. Many retailers and manufacturers offer that option with their products for a nominal fee. If that’s not available, you can have your bolt and barrel headspace checked professionally; likely for less than the cost of a set of gauges. Bottom line: Don’t sacrifice safety for savings.