Slim, compact semi-automatic pistols are deeply embedded in the corporate DNA of Smith & Wesson. The company’s very first semi-auto handgun was a single-stack .35-caliber pocket pistol in the early 20th century, and when it returned to the semi-auto market in the 1950s, it was with the classic single-stack Model 39 in 9 mm. Some of the last of the traditional, hammer-fired, metal-frame, double-action variants in the catalog were the “Chiefs Special” line of chopped-down single-stack pistols optimized for concealed carry.

So when the focus of the company’s duty line of semi-autos shifted from the original DA/SA self-loaders to the new polymer-frame M&P series, the dearth of a slim single-stack in the lineup was felt like a missing tooth in your mouth. Sure, you could get by without it, maybe even get used to its absence, but something that had seemingly always been there was missing.

Therefore, the arrival in 2012 of the new M&P Shield subcompact line was greeted with a level of enthusiasm (to say nothing of sales success) that must have been gratifying in the Smith & Wesson corporate offices in Springfield, MA. People bought the things in droves not only because they filled a market niche Smith & Wesson had temporarily abandoned, but because they carried that classic Smith & Wesson name at a price point that had to have drawn nervous side-eyes from more traditionally price-conscious brands.

The older, compact DA/SA semi-autos from Smith & Wesson served one other role in the company’s lineup that the initial release of the Shield didn’t fulfill, though. The Model 3913 and its .40- and .45-caliber kin served as the basis for a host of more upscale models in Smith & Wesson’s Performance Center catalog line. In retrospect, it should have been obvious that it was only a matter of time before there was a Performance Center Shield.

So, anyhow, back to the present: The Shield has been a hot seller, and I was thinking of buying one myself for those days when I couldn’t CCW my regular heater, a full-size M&P9. Then, out of the blue, I got an e-mail from the editor: “Hey, Tam, want to write up a Performance Center Shield...”

Yay!

“...in .40 S&W?”

Oh...

I don’t necessarily have anything against .40 S&W, mind you. It was what I carried all the way through the ’90s, before my brief fling with the 10 mm and then years of .45 ACP 1911 orthodoxy.

Still, with good modern duty-type loads, I just don’t know that there’s enough terminal-ballistic benefit for me to justify the decrease in “shootability” from the nine. In duty-size guns, like the full-size M&Ps, .40 S&W and 9 mm shoot about the same, sure. But in compacts, like the M&P “C” models, the difference in muzzle flip really starts to make itself known. What would it be like in a truly tiny single-stack like the Shield? I guess I was about to find out.

Other than the “Performance Center” markings, the most obvious clue that this isn’t your everyday Shield are the row of lightening holes that march down the top edges of the slide, three to a side. The front pair of holes, up at the muzzle end, frame the ports in the barrel that redirect gasses upward to help tame felt recoil and muzzle flip. In between those ports is the front sight, loaded with a green fiber-optic rod, and it’s matched by a pair of red/orange rods in the rear sight, creating a crisp, bright, three-dot sight picture.

The parts you can’t see are in the lockwork: The Performance Center adds its own enhanced sear and trigger that give character to the trigger pull I found vastly preferable to the OEM setup. Take-up was minimal and the trigger broke extremely clean at precisely 6 pounds on my RCBS trigger scale every time. The crisp nature of the break would have had me guessing it was a pound or more lighter if I hadn’t read the scale myself. (Then again, I’m one of those people who think the “factory” connector and the NY1 trigger spring is the ideal setup in Glocks, so there’s that.)

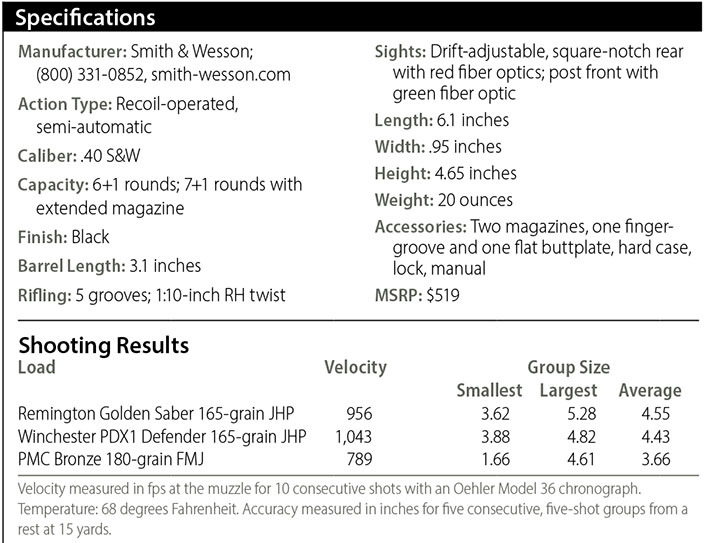

The gun’s external dimensions are the same as a regular Shield: Just a hair over 6 inches long and a skosh under an inch wide. Where it differs is in weight, however. My postal scale read the gun and the empty six-round magazine as weighing 20 ounces, and the empty seven-round magazine added just less than half an ounce.

What makes the Shield appealing to the small-of-hand is the circumference around the trigger. A lot of hay gets made measuring the straight-line distance from the left grip panel to the right or from the trigger face to the backstrap, but what will really tell you if a handgun is going to be comfortable to people with smaller mitts is measuring the circumference from the trigger, around the backstrap, and back to the trigger with a soft cloth measuring tape. Here’s where the Shield comes up almost a full .75-inch smaller than even an M&P9 Compact with the smallest backstrap.

Then came the moment of truth: Busting some caps on the range.

First, I think fears of porting are overblown. You’ll hear all kinds of things about getting blinded by the flash from the ports and whatnot, but the muzzle flash from a 3.1-inch .40 S&W is what it is. A couple more little jets of flame are hardly going to be the make-or-break factor one way or the other in how dazzling it is to your night vision. The sole real concern is ejecta from the ports when you’re shooting from retention, and this will be contingent on body type and how you hold the gun. I roll mine pretty far outboard and haven’t noticed much, but others may. Your mileage, as they say, may vary.

Now, earlier in the article I wrote about how I’d come to prefer 9 mm over .40 S&W, and the earliest range sessions were a reminder why. While the difference in perceived recoil between the two is minimal in a service handgun, it’s a really big deal in a gun with a 3-inch barrel and a grip like a moderately textured Popsicle stick.

The Shield 9, even in its vanilla, unported configuration, is a reasonably pleasant gun to shoot. Conversely, putting much more than a box or two through this .40 at a sitting was a chore. One friend found herself frequently having to rebuild her grip on the gun between shots and, while I didn’t find it quite that bad, I still wouldn’t want to spend the afternoon shooting tin cans with it. To drag out a hoary old gun review cliché, “recoil was brisk but manageable.”

The other problem was with accuracy. Since, despite its diminutive size, this is a grown-up gun in a centerfire caliber with good sights, I didn’t ask for any special dispensation and set out to shoot 25-yard groups with the pocket-size Shield like it was a service-size auto. That was in addition to 15-yard testing done to compare it to like-sized pistols. Actually, I recruited a co-worker, Zach Rogers, who is known for his ability to split business cards shooting over his shoulder with a mirror, to sit down and start shooting 25-yard groups one morning.

I want to say that accuracy was problematic, but it wasn’t. Accuracy was, except for a couple of groups with obvious fliers, about what I’d expect from a lightweight pistol with a stubby barrel in a chambering that, let’s face it, isn’t widely used in the bullseye community.

Three different loads were tried at 25 yards, from CCI Speer, Hornady, and Federal. The most accurate results came from the 175-grain Hornady Critical Duty, which averaged 5.6-inch groups. (Once again, Hornady’s 175-grain Critical Duty impressed me with its consistency. The 10-shot string had an extreme spread of 30.61 fps and a standard deviation of only 9.38 fps. That’s tight.) I guess since I’ve already used “brisk but manageable,” here’s where I trot out the saw about “acceptable combat accuracy.”

Chrono testing showed another minor downside to the stubby, ported barrel: The Speer LE Gold Dot Duty ammo that’s rated at 1,200 fps out of a service-size semi-auto clocked in at an average of only 1,063 from the ported Shield.

Still and all, the gun worked, and worked fine, having no malfunctions over the course of more than 500 rounds of varied ammunition, despite a complete indifference to cleaning the thing. It didn’t display bullseye-match accuracy at 25 yards, but could keep them all in the 10-ring easily at 21 feet. At 15 yards using hollow points from Remington and Winchester, and PMC Bronze FMJ flat-points, the little semi-automatic consistently grouped in the 3- to 5-inch range, the occasional flyer notwithstanding.

It was eminently concealable, the sights were good, the trigger was just dandy. If there seems to be any kind of negative vibe coming out in my writing, it’s only because I kept thinking to myself “If this gun were a 9 mm, they’d have to drive out here from Virginia and wrestle it away from me.”

So who is it for? Well, first and most obviously, if you don’t believe that “Nine is Fine,” here’s your pocket pistol. With an MSRP of $519, it’s the value standout of the class. The 800-pound gorilla of the polymer personal-defense pistol market doesn’t even make a .40 in this size and weight class, and the ported Shield is much easier to shoot than comparable .40-caliber offerings from other manufacturers.

The second, less obvious, customer is the LE officer working for an agency that provides .40-caliber duty ammo. Sure, the .40 is less fun to shoot than the 9 mm, but not enough less fun to outweigh free ammunition. If my bosses were providing me with the BBs, I could learn to stop worrying and love a little extra muzzle flip.

Final Verdict: Would buy if I were in a place where .40 S&W was free, or if I still believed in caliber voodoo, but it mostly made me wish it were a 9 mm so I could not send it back and live happily ever after with a smokin’ hot pocket semi-auto.

New Laser-Cut Patterns from Talon Grips

New Laser-Cut Patterns from Talon GripsOne of the best products we have found for improving purchase on polymer-frame pistols is Talon Grips. Originally die-cut, the appliqués are available in a choice of granulate (think skateboard tape) or rubberized. The former is best for duty, open carry and extreme conditions, while the latter is excellent for concealed carry. Affordable and fairly simple to apply (follow the instructions exactly, though), the best thing about Talon Grips is how effective they are at giving you a firm hold on your gun, one that resists the torquing that is a problem with lightweight, polymer pistols firing self-defense calibers.

Talon has now improved on its already fine products by introducing laser-cutting to all its grips. The dies Talon had been using were complicated, difficult to make and problematic to modify if a pistol model changed. And, though the grip designs were generally marvels of fitting, die-cutting could achieve only limited intricacy. The company’s new laser-cut grips can and do feature more precise, intricate patterns that make for more precise fitting than was previously possible. The Smith & Wesson M&P Shield, Springfield’s XD pistols and Glock’s entire line are the latest pistols for which the new, laser-cut patterns are offered. Moreover, additional popular pistol models are being added all the time.

—Daniel T. McElrath

MSRP: $19.99; talongungrips.com