Whether a defensive shooter or a competitive shooter, you strive for that higher skill level. However, not all skills are purely physical. Shooting well at the upper levels, much like any professional sport, is more mental than physical. What are three of the most useful mental approaches employed by shooting professionals to enhance their skills?

In the world of defensive shooting, regardless of which agency or organization for which you may work, you must minimally pass a firearm qualification in order to carry and/or operate a firearm as part of your job responsibilities. Attending an academy or basic-skills train-up should prepare you to pass the minimum qualification standards set by that agency’s governing body.

Going through a federal agency or any civilian law-enforcement academy, you are usually issued a firearm and corresponding equipment—for example, a holster and magazine pouches for that handgun. Utilizing your issued gear, you are then required to pass an official qualification with a minimum required score. Once you’ve accomplished this task, you have checked the box and may go forth and conduct your duties as assigned.

Per industry standards, the very first budget to get cut in any agency or department is the training budget. Outside any specialty team, odds are you may not be eligible for in-service training and/or your annual qualification may be the only “time on gun” you are officially allocated.

It has been my observation over the past three decades of service in the professional, hard-skills world that less than five percent of all law enforcement and armed federal employees train on their own time and on their own dime. It’s a very small percentage and although encouraged, few officers or agents outside that percentage are motivated to do so. The scant few who do pursue the gold ring of shooting beyond the requirements of minimal qualification must do so outside the box—external to the confines of an institutional skills-development program or schedule.

On the opposite end of the practical-shooting spectrum stands the competitive shooter, who may or may not be a Fed or law-enforcement employee. Although not required to pass any organizational qualification to compete, there are certain structured competitive-shooting organizations—like the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), the United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA), the International Defensive Pistol Association (IDPA) and others—where a shooter may shoot a posted “qualifier” to attain that particular organization’s ranking. A ranking example may be something along the lines of “Master Class,” “Grand Master,” “Class A” or “Class B” and the like.

The competitive shooter is motivated to shoot well to win matches. Either way, whether you’re a defensive shooter or a competitive shooter, anyone who desires to shoot well—better than their current skill level—has no choice but to step up their game beyond their qualification level. Skill-building, resulting in greater performance, turns out to be confidence building. Concordantly, there are three mental approaches used by professionals that can help build skill, improve performance and raise confidence.

Discipline

It is said that “learning occurs outside your comfort zone” and nothing could be more accurate for those seeking to shoot well. The first and foremost mental approach to shooting excellence is sustaining the motivation necessary to fulfill such a long-term and challenging objective. In other words, getting your head into the game or committing mentally as the amount of time (range, dry-fire, classes, etc.), expense (ammunition, range gear, targets, etc.) and level of commitment can be daunting.

Depending upon what skill level you may be targeting, it could very well warrant training seven days a week for months on end—or even years. Your passion will carry you only so far and when passion wanes, all that remains to carry you forward is your mental discipline. For example, even if you can dry fire for only 5 minutes, that’s better than putting in zero training for a day. It takes mental discipline to do that on a consistent and ongoing basis.

The second application of mental discipline is you must be willing to accept the fact that your gains will be smaller and harder earned. The higher you climb up the shooting-performance ladder, the smaller your gains. Mental discipline is not expecting big or quick improvements, but seeking small improvements one day at a time. Gone are the days and weeks of significant chunks of skills development. For example, if you need to gain .17 second to pass a certain shooting standard and you’re not at that skill level, be prepared for a long haul. You may be able to catch lightning in a bottle one or two times here and there, but realistically it could take weeks or even months to chop that time down to where you can default to it greater than 85 percent of the time and on demand. It is important to note that such small successes are not stopping points, but stepping stones.

In your next-level training, you may be able to achieve a benchmark one out of every 100 tries. Then, over time, one out of every 80 tries and so on, until one day that performance triangle is inverted where “an expert can get it right most of the time, a professional can’t do it wrong.”

The third application of mental discipline is you must be willing to accept the fact that you will experience more failures than successes. “The master has failed more times than the novice has even tried”—speaks volumes to those seeking to shoot well. If you want to improve, you must accept those mistakes (which are critical to the learning process) as part and parcel of your learning curve and to remain emotionally detached from failure.

Making mistakes is conducive to skill building because you gain greater clarity of contrast between “what it takes to do it right” and “what it takes to do it wrong.” Suffering errors is a positive indicator that your practice is reaching deep enough to affect your skill level. The deeper your practice, the better you get.

Nothing short of discipline will provide you with the grit it takes to remain motivated, expect smaller gains and accept the sheer volume of errors necessary to make such gains. At the upper levels of shooting skills development, it is often said by Master and Grandmaster instructors “you may have the skill, but lack the discipline to apply that skill.” It turns out that discipline is not only a mental approach, but also a necessary component of personal development when it comes to physical performance. Having the mechanical skill to do something difficult is one thing, but having the discipline to convert that mechanical skill to on-demand performance is something with which every shooter climbing the technical skills ladder must inevitably grapple.

Process

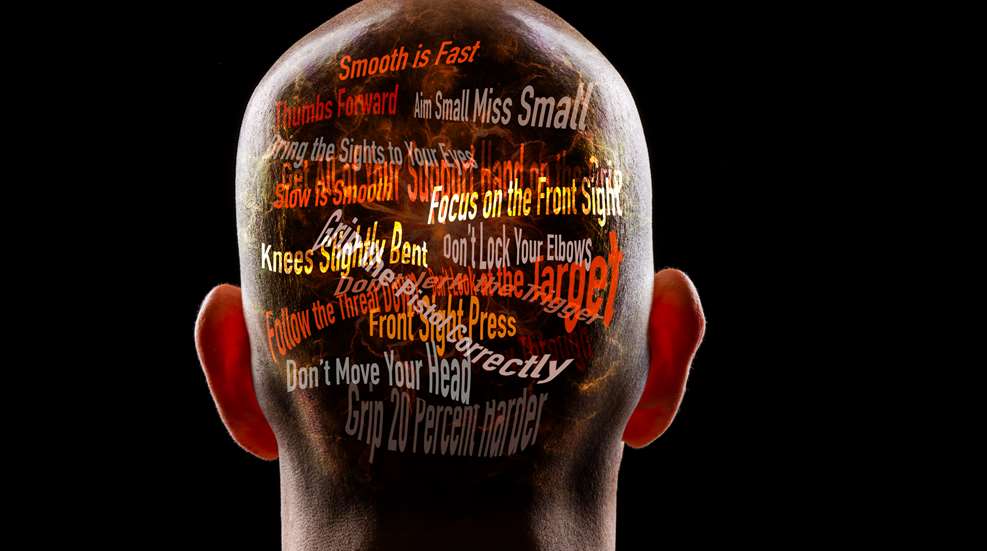

A second approach to shooting proficiency is to mentally choose between “trying to be better” or to follow a specific process. According to champion shooter Rob Leatham, the shooting process is defined as nothing more than aligning the gun with the visual center of the intended target and pressing off the round without moving the muzzle. It’s a very simple process, but not easy to accomplish, especially when tasked with meeting the demands of master-level speed and accuracy.

Given a vetted shooting process, mentally, you can choose to follow that process or “just try and shoot better.” Trying to shoot better with no process has no guidelines, no parameters and no metrics by which you may base your training regimen. Following a clearly defined process, you can expect the same results every time. If you hold the gun well enough that you do not disturb alignment throughout breaking the shot, then you cannot miss the target. Errors in accuracy or speed occur when something in the shooting process breaks down.

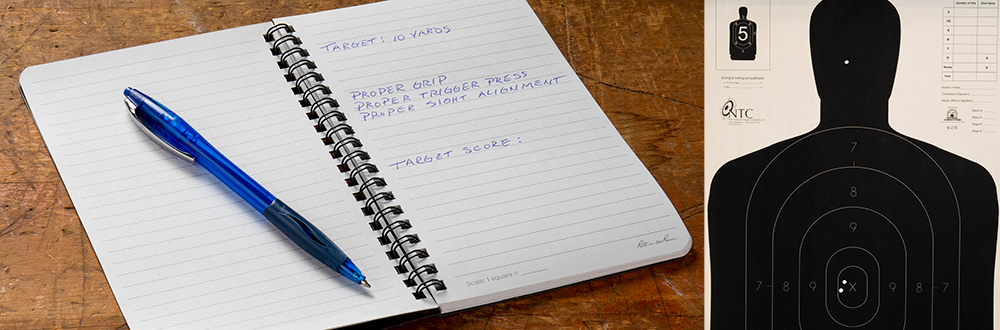

Take a “failure drill,” for example. That is two rounds to the 6x11-inch “A-box” body (upper thoracic cavity) followed by one round to visual center of the head. You can run this at anywhere from 7 to 10 yards. The drill is to draw your handgun from the holster and establish a good enough grip to deliver two rounds to the center of the body followed by one to the head.

Here, you can apply one of two mental approaches—“try harder” or “follow the process.” If you choose to follow the process you must perform a good presentation where the sights/dot land in the middle of the body-target A-zone, at which time you press off two rounds followed by muzzle movement toward the head, where you deliver a third round without disturbing the sights from the visual center of the head box. If one thing falls out of the process, such as misalignment, change in grip pressure and the like, then you will miss. If you do everything correctly, then you can’t miss.

If you chose the other mental approach to “try harder,” how exactly does one do that? What are the technical parameters of “trying harder,” especially with no process? What causes a miss and what causes a hit? How can you clearly illustrate or understand the contrast between success and failure and, more importantly, what exactly can be learned from trying harder?

Control

A third and equally important mental approach to shooting well is a matter of control. Either you control the shooting, or the shooting will control you. To facilitate shooting control, one must master both mechanical as well as mental control.

Attention to detail is a big part of what it takes to become successful at any skill—especially the art and science of shooting well. Part and parcel of any shooting process is to control every aspect of gun handling to result in the purpose of shooting, which is to hit what you are aiming at. This is commonly referred to as mechanical control. Good mechanical control means that you have control of the sights, the trigger and every effect of their operation such as presentation, alignment, recoil, transitions (movement from one target to another target) and splits (multiple rounds on the same target).

Mechanical control translates to trigger, sights, hold, grip and many other technical components of shooting well. Trigger control is a complete study unto itself with multiple trigger positions and trigger finger positions. Control of the sights starts with being able to visually follow the sights before, during and after breaking a shot. If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it. Did they stay in the six- to 12-o’clock position? How high did they rise during the shot? Did they return directly to the target, or did they require correction to return to target? Hold control as defined by the NRA is to control the combined movement of the shooter and the firearm on the target. Grip control is the skill whereby you have gained the ability to maintain the exact same grip pressure between breaking any number of shots and on any number of targets or target arrays.

In addition to mechanical control, and paramount to shooting well, is control of what goes on between your earmuffs. Tier-one government gun carriers and Grandmaster shooters alike will tell you that the shooting process must become subconscious. The best coaches in the business agree that there’s not going to be instant gratification, and everything boils back down to training—doing it over and over again. Correct repetition is the key to learning, and the importance of repetition until the shooting process is pushed to the subconscious level cannot be overstated. The key to that automaticity is to get out of your own head. Let the process do what it was designed to do. That is much easier said than done, as some shooters tend to become over-analytical. Mechanical control and mental control are the keys to developing that automaticity.

Shooting prowess is more mental than physical. The three most useful mental approaches used by shooting professionals to enhance their skills are being disciplined, following a process and having control. If you can adopt any one, two or all three of these into your shooting practice, then you would be taking the very same approach as the very best in the business.

Adopting the same type of mental approach into your personal-defensive training as those who do it for a living may have a profound impact on your skills development, shooting performance and personal confidence. Having a plan in place, keeping the mental discipline to keep practicing and not being dissuaded by failures and misses will bring success. Alternatively, however, you always have the option to just try harder.