Tier-one shooters worldwide know that speed is nothing more than a byproduct of efficiency, and that accuracy is a byproduct of control. Anyone who earnestly trains to be a better on-demand shooter can attest that developing optimal efficiency and control is not as easy as it sounds.

One of the most overlooked training elements of developing such elite shooting skills is self-diagnostics. When it comes to mastering true self-diagnostics, most shooters don’t know what they don’t know. Where do you even start? What do you look for? How do you know exactly what needs to be remediated? How do you precisely remedy such deficiencies and using what tools?

Since the earliest times, it was known that “the target tells the story.” However, it wasn’t until the aftermath of the Second World War, when millions of veterans returned home with extensive firearms familiarity, that military and law enforcement institutions quickly realized that wartime training, focused on mass mobilization and battlefield marksmanship, was insufficient for peacetime policing and evolving Cold War needs. The U.S. Army and allied militaries began revising doctrine away from trench and mass-infantry tactics toward small-unit firepower and precision shooting.

The classic “pie chart” shooting-correction target emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s as a visual tool for training, particularly for Bullseye marksmanship. Popularized by TSgt Edmund Abel’s 1962 American Rifleman article, “Pistol Targets ‘Talk,’” the chart segmented a bullseye into labeled regions, each corresponding to a specific error such as “jerking the trigger” or “heeling the grip.” Circulated widely through NRA, law enforcement and military publications, it embodied the mid-century belief that the target itself could “talk,” offering shooters direct diagnostic feedback in the absence of a coach.

Though once a cornerstone of formal pistol instruction, the chart is now regarded as more of a historical artifact than practical remedy. Its simple visual mappings provided a useful starting point for one-hand, Bullseye shooters, but modern disciplines demand richer feedback: live-fire qualification drills, video analysis and instructor observation. In this light, the pie chart stands as a reminder of mid-20th-century training methods, an icon of its era, but ultimately eclipsed by more precise contemporary diagnostic tools.

Fast-forward to the development of today’s cutting-edge performance shooting. Such exceptional on-demand shooting skills are now a requirement for designated Tier-1 military and law enforcement assets. Thus, modern performance-shooting diagnostics represent a decisive break from the static, two-dimensional marksmanship methods of the mid-20th century. They offer a data-driven, empirically verifiable window into shooter behavior under practical conditions.

The likes of slow-motion video, electronic shot timers, recoil sensors, eye-tracking systems and pressure-sensitive grips now allow instructors and athletes to dissect performance at the millisecond scale—capturing inefficiencies in draw stroke, trigger control, sight alignment and recovery that the naked eye cannot reliably perceive.

Unlike the old pie-chart targets, which reduced complex motor errors to shallowly analyzed shot clusters, modern diagnostics isolate causal mechanisms of error and provide repeatable baselines for skill progression. This shift has elevated firearm training from rote qualification to a genuine performance science, enabling shooters to refine technique with the same rigor found in elite athletics or aviation. In doing so, it closes the gap between theoretical marksmanship principles and operational competence, ensuring that skill development is not only accelerated, but also measurable, transferable and resilient under duress.

The rule of thumb for such diagnostics is “you can’t fix something you can’t see.” Step one in any self-diagnostics training environment is to identify a shooting component that needs work. As with all shooters seeking to expand their skills envelope to the next level, there is always more than one element that requires attention; so how do you know which one to address first?

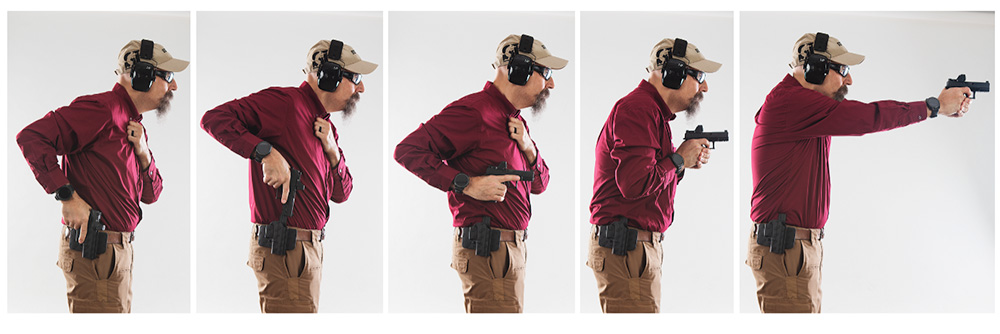

In the modern diagnostics vernacular, such deficiencies are called “fruit,” and those repetitive observable errors are referred to as “lowest-hanging fruit.” An example might be something like drawing a pistol from the holster and erroneously tracing the muzzle forward past the holster toward the ground before pointing it directly toward the target. If you observe a shooter doing this, say 80 to 90 percent of the time, then this could be identified as lower-hanging fruit.

Even though there may be more than one piece of fruit, you’ve got to start somewhere, so just pick the one that bugs you the most.

The overarching self-diagnostic process is to identify, isolate and eliminate inefficiencies, and eventually rebuild the skillset with less margin of error and greater consistency. All of this can be tracked with data collection and then analyzed (evaluated) over a set period.

In the case of the “bowler,” where the shooter draws from the holster directly past the holster to the ground as opposed to the target, they may not even be aware they are doing it. When first hearing it from a coach or fellow observer, the shooter will most likely react defensively: “Hey, no way; I’m not doing that!” So, that’s when you film it with their cell phone so they can see exactly what you’re describing. It is upon this realization “Hmmm, I never noticed that …,” a critical remediation step, where the shooter finds the requisite motivation to work on it.

Taking this specific bowling issue, the consummate diagnostician would break down the movement into three subcomponents. Subcomponent one might be the initial grip on the holstered gun. The shooter may be directed to focus intently on the visual center of the intended target ahead of the draw, then, mentally connected to the shooting process, establish a positive strong-hand-only grip in less than a half-second. Just this one sub-element comprises three parts: being mentally ahead of the process, visually focused and mechanically programmed for rapid acquisition.

The diagnostician demands isolating just that one sub-element and repeating it until it can be executed more than 80 percent of the time, without error. Once the shooter can sustain this repeatability, they can move on. The next piece may be clearing the muzzle from the holster, pivoting the muzzle toward the target and then moving into a two-handed firing position along a straight line to the target avoiding any unnecessary or added muzzle movement. Again, three sub-elements: clear the holster, pivot the muzzle and then marry strong and support hands, all while keeping the muzzle trained directly on the visual center of the target, thus avoiding any “bowling” motion.

Yet again, the diagnostician demands isolating just that one sub-element and repeating it until it can be executed greater than 80 percent of the time with minimal error. Once this repeatability is sustained, this second three-part component may then be appended to the first. Even though the shooter may be able to execute the first part and the second part in isolation, the third part of this remediation is the skill to execute the continual flow from the first to the second.

Viewed from the diagnostician’s perspective, these are three distinctly separate skills. The first subcomponent skill, the second subcomponent skill and the third skill which is the connection of the first two as a single flow of movement—mental and visual connection to the target, positive initial grip, clearing the holster, pivoting and welding both hands together with the muzzle already trained on the target as opposed to bowling. Isolate, eliminate and reconstruct. Problem solved.

The statistics may include some primary-component repetitions to achieve an 80-percent standard in addition to the number of second-component repetitions to reach the minimal 80-percent repeatability standard. The higher the desired skill level, the higher that percentage. In the elite training community, this is usually set at 95 percent for those shooting at the very leading edge.

Another example might be recoil recovery. The shooter is found to consistently shoot either left or right of the intended target on the second shot. Observing and identifying this as the lowest hanging fruit, the diagnostician sets out to remediate.

Step one: isolate. The erroneous second shot is a symptom of an earlier deficiency in making the gun optimally respond with the muzzle moving strictly along a straight line, up-and-down, 12-o’clock to six-o’clock trajectory.

The shooter is instructed to observe the sights (irons or red dot) from the time the first shot is released to the time their trigger finger is reset at the wall in preparation for the second round. Particular attention should be paid to movement of the sights up and down. On the way up, which way did it go? Straight up (12 o’clock) or left (10 or 11 o’clock) or right (one, two or even three o’clock)?

If it is the case that the sights do not move straight up on initial impulse, then manipulate the firearm in such a manner that the next time and 80 percent of the time it finds its way straight up. One isolation drill may be to simply fire a single round and immediately get back on the wall forcing a six- and 12-o’clock, straight-line trajectory. Once this is accomplished, the shooter should then see their sights either on their way down to the intended target area or precisely within the center of that target area where—then and only then—may they send the next round. Yet again, this is the second component.

Each subcomponent is isolated and repeated to the 80-percent standard, and when that standard is attained for each, then combine the two skills to create a third—the rapid and repeatable execution of the two sub-elements sequentially adjoined. Identify, isolate, work out inefficiencies to the 80-percent-repetition standard and then reconstruct the overall skillset by combining the now-remedied subcomponents.

Once you’ve cleaned up all the lower hanging fruit you could find, the next step in the diagnostics process is to use one of the most powerful and effective upper-skills development tools available to any shooter in breaking through to the next skill level: errors.

You cannot grow beyond your current skills envelope if you don’t step outside your comfort zone by making mistakes. If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not pushing yourself hard enough as a shooter seeking to progress. To err is to induce opportunity.

Errors are the most powerful teachers in shooting because they forge an immediate and unambiguous link between cause and effect. Each misplaced shot encodes a wealth of diagnostic information about grip tension, trigger press, visual focus etc.—information that a perfect bullseye often conceals.

When a round lands off target, the shooter is compelled to interrogate the precise moment of—and reason for—failure, whether it was anticipation of recoil, change in grip pressure or losing visual discipline. What might appear as failure is, in reality, a feedback system: an error is a traceable map that points directly to the root cause. In this way, mistakes evolve from frustration into actionable data, providing far sharper insight than success ever could.

True skills development in on-demand, performance shooting is therefore not about endlessly repeating what went right, but about systematically addressing what went wrong.

When approached with discipline, each error becomes a stepping stone toward mastery: Analyzed, corrected and internalized, it accelerates adaptation and ingrains resilient tech- nique, building on-demand ability.

This understanding also highlights the profound shift from traditional training to modern performance shooting. In the classic Bullseye era, every miss was treated as a penalty—deducted from a scorecard and internalized as failure. The system prized repetition of perfection, but offered little clarity about why a shot went astray.

By contrast, modern performance training reframes errors as diagnostic events. A shot breaking low and left is not simply a “miss,” but evidence of anticipation or grip collapse, and with the aid of timers, sensors and video, that deviation becomes measurable data that points to an exact mechanism requiring correction, data that can be analyzed and utilized to clearly demonstrate progress.

The result is a philosophical and practical evolution: Modern diagnostics, to include data collection, analysis and sustainment, encourage shooters not to fear mistakes but to mine them. In this diagnostics model, the miss is not the end of performance, but the beginning of refinement—transforming error from enemy into essential raw material. What was once a mark of failure has now become the engine of progress, making error not the obstacle to mastery, but the very path by which it is achieved. Modern tools—timers, sensors and video—allow errors to be dissected with athletic rigor, turning every deviation into a measurable, correctable pathway forward.

The elite diagnostician knows that each error isolates a problem, each correction eliminates inefficiency and each reconstruction builds a more durable skill. This recursive cycle—identify, isolate, refine, repeat—is the crucible in which the modern self-diagnosing shooter is forged.

Speed emerges as the natural consequence of efficiency, accuracy as the byproduct of control and error as the indispensable raw material of both. In the end, the shooter who learns to mine mistakes rather than dread them discovers not just how to precisely hit the target, but how to build a system of performance that is measurable, adaptable and repeatable—the true mark of a master-at-arms.