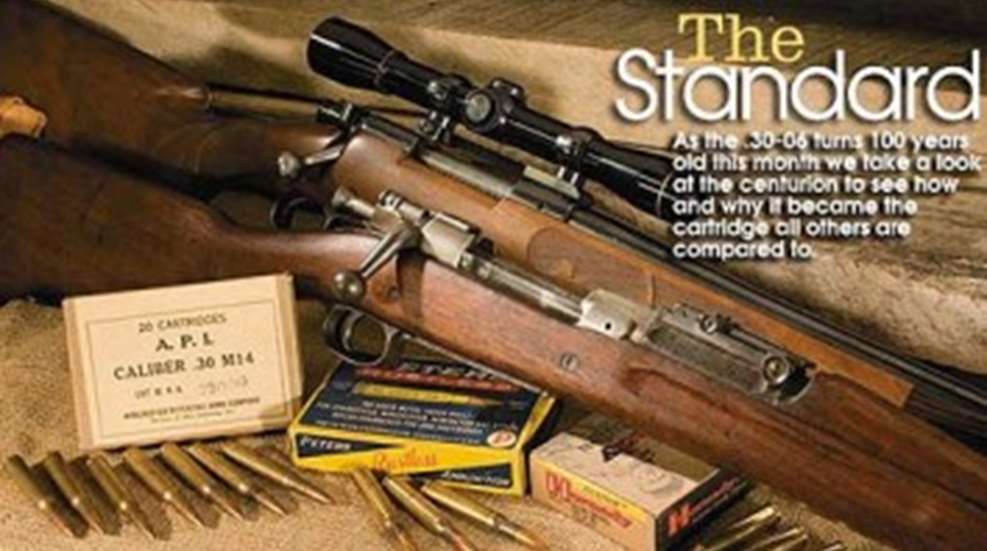

On October 15, 1906, when the Small Arms Board signed off declaring the "Caliber .30 Ball Cartridge, Model 1906" as the U.S. military's official cartridge, I wonder if it gave any thought as to the impact its decision would have on so many people for so long a time. One hundred years later the .30-06—as it is known today—remains the standard by which virtually all other rifle cartridges are judged. Be it military or sporting, where subsequent designs are compared in terms of power, trajectory, velocity—even availability—the benchmark remains the .30-06. Among students and devotees of the rifle the question begs: What is so magical about this cartridge? Why is it the standard that all others are measured against? To answer this, we need to look back a little further than 1906.

The story dates back to somewhere around 1888 when Army Ordnance began looking at reducing the caliber and weight of ammunition its soldiers carried afield. At the time a U.S. soldier carried a .45-caliber rifle, carbine or musket. We know it today as the .45-70 Government and the Trapdoor Springfield. The old "ounce of lead" was a proven man and horse stopper, but its trajectory was beginning to be outclassed by more innovative rifles and cartridges from Europe. Repeating rifles were blowing away their single-shot counterparts on the continent and around the world. Nitrocellulose-based smokeless powder was being perfected, and it became possible to launch bullets much faster than before. Too, it was learned bullets did not need to be the size of a man's thumb in order to be effective. The new high velocities gave bullets far more energy, and ballisticians and ordnance officers learned how this dramatically affected terminal performance.

By 1890 the .30 caliber was established, and experimental rounds featuring 230-grain copper-jacketed bullets with four lubricating grooves were submitted to the Small Arms Board at the Springfield Armory for evaluation. Problems with the jackets stripping due to the increased velocity were addressed by altering bullet diameters and jacket materials—everything from German silver to steel were used. Eventually the Small Arms Board adopted the "Cal. .30 Ball" cartridge with a 220-grain, cupro-nickel-jacketed bullet in a "flanged" or rimmed case backed by 40 grains of smokeless powder at 2,000 feet per second. The rifle platform to launch this was the 1892 Krag-Jorgensen, and today we know this cartridge as the .30-40 Krag. It was obsolete almost as it was issued.

The United States got involved in a little dido down in Cuba in 1898 called the Spanish-American War. American soldiers fought valiantly with their Krags and eventually wrested control of the Caribbean from Spain, but not before getting their butts shot to pieces from a rifle called the 1898 Mauser chambered in a wicked little round, the 7x57 mm Mauser. The Mauser proved to be an extraordinarily accurate and reliable rifle—simple to operate and quick to reload—and its cartridge reached farther and hit harder than the Krag round.

We Americans do not take a whippin'—even one in which we are the ultimate victor—well. At the same time we are unalterably convinced we build the biggest and best of everything, but at that point in history we had a problem. The Mauser Model 1898 and its dinky, little 7-mm cartridge was pretty much state of the art at the dawn of the 20th century. Loveable rogues that we are, we simply ripped off the Germans. On June 19, 1903 the "United States Magazine Rifle, Model of 1903, Caliber .30" was adopted. Chambered for a .30-caliber cartridge launching another 220-grain bullet in front of 45 grains of smokeless powder—it is also known as the .30-45—300 feet per second faster than the Krag, the rifle and cartridge were simply Yankee renditions of the German rifle and cartridge. The patent infringement was so blatant the U.S. Government eventually had to pay a royalty to Mauser. But what became known as the .30-03 simply didn't cut the mustard.

The Point Is…The 7x57 mm Mauser used a 175-grain "spitzer" bullet at 2,300 feet per second. Spitzer is German for "sharpen" or pointed. The spitzer shape cut through the air better than the round-nose bullets of yore—the same style bullets we clung to in the .30-40 Krag and .30-03 cartridges—thus it had a flatter trajectory and more effective range. We simply had to lighten up.

In April 1905, experiments with German S-type (for spitzer) bullets began at the Frankford Arsenal. A 150-grain bullet could be driven to 2,700 feet per second, but accuracy in the 1903 Springfield flagged. It didn't take too long to figure the 1903 Springfield rifles had throats that were too long for 150-grain spitzers. There simply was too much opportunity for the bullet to get cockeyed making the jump from the case to the bore. Too, the case neck of the .30-03 was unnecessarily long for the short bullet. The decision was made to shorten the case by .07 inch and recall the inventory of rifles to have their chambers shortened by turning a couple of threads off the barrel and re-headspacing it.

What we now call the .30-06 endeared itself to American shooters during World War I. Yes, sporting men were shooting the government cartridge in Model 1895 Winchesters as early as 1908, but when we sent somewhere around 1 million Americans to Europe to calm things down our guys got a healthy dose of modern rifle practice and technology. When they returned to hunt deer and other game, they wanted a .30-06. Remington was first out of the gate with the Model 30 in 1921, and Winchester came out with the Model 54 in 1925 in .30-06. Custom gunsmiths began "sporterizing" surplus 1903 Springfields and converting liberated, as well as commercial, 1898 Mausers to the caliber.

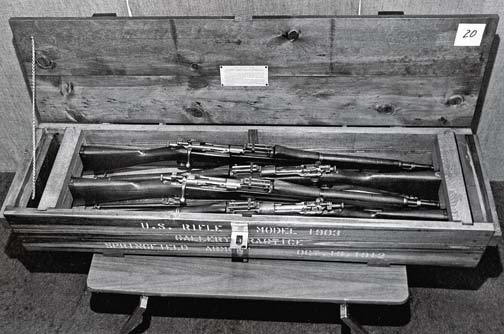

Surplus Springfields could be purchased by NRA members for as little as $15 until about 1932. The heavier and more cumbersome Enfields, commissioned during the Great War to subsidize the huge demand for rifles, also joined the surplus market. Decades later in the early 1980s I came to curse the Enfield after sporterizing a couple of them during a stint as a gunsmith in Afton, WY, and spending more time than I'd care to admit grinding off the "ears" or rear sight support on the original in order to profile the receiver to be drilled and tapped for modern scope mounts. Many of these Enfield and Springfield rifles were converted to other calibers, and more than a few wildcats were based on the .30-06 case. But our guys had a lot of well-founded faith in the .30-06, and though there's no way to ever exactly quantify the inventory of calibers, I suspect a clear majority remained chambered for the government round.

Government round—that more than likely explains the almost universal lure of this cartridge, as well as the disdain for it by contrarians. Remember, the .30-06 was not only the caliber of the 1903 Springfield and 1917 Enfield, but the M1 Garand, BAR and a host of light machine guns, along with the thousands of sporting rifles like the Remington Model 30 and later the Models 720, 721, 725, 700 740 and 760. Winchester, of course, started chambering the Model 95 lever action in .30-03 in 1905; then the .30-06 in 1908, and, of course, the Models 54 and 70 later. Savage made its bolt-action Models 40 and 45 in .30-06, and a cornucopia of foreign makers and contract manufacturers from Browning to Mauser and Sako made rifles chambered in .30-06.

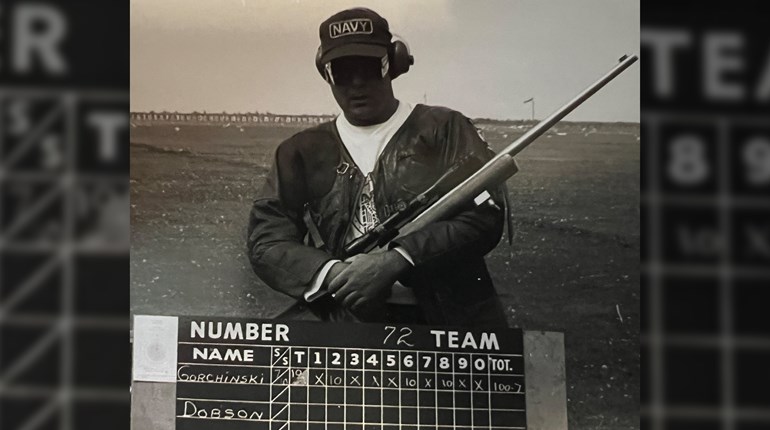

Christened All-Around CaliberBy the 1950s the .30-06 was considered the standard sporting cartridge—whether the sport was NRA High Power at Camp Perry or hunting the game fields. To be sure there were other cartridges of varying levels of popularity. The magnum bug was certainly blooming. As the post-war economy provided Americans with more discretionary income and time, experimenters and basement ballisticians did their best to unseat the old '06 from its throne, but all those rifles and the seemingly endless supply of cheap ammo ensured most people would be shooting and hunting with the .30-06. It became known as "the all-around caliber."

"Google" .30-06, and you'll get about 92 million hits in .06 second. Its history is chronicled as well as its uses all over the world from the target range and battlefields to virtually any place game animals are hunted. The .30-06 is simply that universal.

First LoveIn 1974 I borrowed a sporterized 1903 Springfield with a Lyman Alaskan scope from a friend and went deer hunting for the first time in the California Sierra Nevada mountains. I didn't know squat about deer or hunting then but it seemed like the thing to do, and a .30-06 seemed to me the thing to do it with. I came back from that solo hunt without a deer, of course, but I was determined to succeed. With tax return money from a menial job, the following April I strode into Cole's Sporting Goods in Inglewood, CA, and bought my first centerfire rifle—a Winchester Model 70 in .30-06—and some reloading dies.

For another four years I shot, reloaded and shot some more. I restocked the Model 70 from a blank I bought from the old Reinhart Fajen's through the mail. The more I reloaded and shot, the more I wanted to shoot. Still deerless—I had no mentor to teach me how to hunt—I went at every opportunity.

I packed everything I owned—about two dozen guns, some reloading gear, a handful of tools, a haphazard array of camping equipment and a Brittany named Boone—into a dilapidated trailer behind a used four-wheel-drive Dodge Power Wagon and moved to Wyoming in 1979. A smattering of jobs kept gas in the truck and powder and bullets for me to shoot. I lived hither and yon up and down Star Valley Wyoming, shooting a lot, hunting as much as possible.

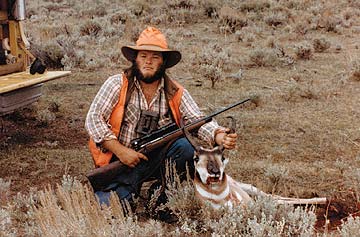

On a cool morning in September 1982 Bud Silver and I were a few miles east of Daniel, WY, on the opening day of the pronghorn season. Shortly after dawn we came across a small herd of does. I picked out one that was broadside and dropped it in its tracks from a distance of about 275 yards. A few hours later while we were eating our lunch, a buck wandered our way, and I killed it with another single shot from about 350 yards. Finally, I was blooded.

Two weeks after the pronghorn hunt Brandt Clark and I were on horseback along the Middle Ridge above the Greys River. It was opening day of the elk and deer season. He, too, was carrying an '06, and as we stepped out of an aspen thicket where we had tied up the horses we saw two mature bull elk eyeing each other and a herd of cows. The cows spotted us and began to nervously mill about. Then one bull some 125 yards distant saw us and wheeled on its hind legs. I threw up my Model 70 and shot at the forward shoulder. All hell broke loose with elk running everywhere. My buddy started hammering the other bull as it ran across the little meadow. The bull I shot was running directly away from me, and I didn't want to try a Texas heart shot, but after going maybe 25 yards, it suddenly stopped and collapsed. Thirty minutes after opening light we had two mature bulls on the ground—both killed neatly by .30-06 rifles. My bull—a 6x7—was hit just forward of the point of the left shoulder. The bullet traveled the length of its body and blew up the femur of its right hip. Brandt's 6x6 bull took four solid hits from 165-grain Hornady Spire Points before it gave it up. Any one of his shots would have done the job, but the bull was running and full of adrenaline.

I left Wyoming in 1985 and began hunting other states in the West. About 1987 I ran across an older gentleman with a 1955-vintage Model 70 Featherweight in .30-06. He could not hunt anymore and told me, "I just can't stand the thought of that fine, old rifle just setting in the closet getting nicked and rusting. I want to make sure whoever gets it will hunt with it." We struck a deal. He was tickled to get about twice what he paid for the rifle new, and I was nearly in rapture to pay only about half of what a pre-'64 Featherweight was going for at the time. I did a little trigger work on the old Model 70, stuck a 4X Leupold on top of it and took it to the range. Happily, it preferred the same handload that my other Model 70 liked. Between the two rifles I've killed more deer, elk and wild pigs than space here allows me to chronicle. Perhaps a couple dozen coyotes have had the misfortune of running across me when I've had one of those rifles with me.

Then I got into the biz…the outdoor writing biz. Rifles started going through my hands like water, as I tested and hunted for the magazines. I still haven't got my fill of it. But last year I decided I needed a retro-hunt—something to bring me back from whence I came and help provide perspective. One of my closest friends and I found a mule deer hunt in South Dakota that didn't require us to be in the condition of a triathlon competitor to get to where the deer live.

There was but one rifle to take for this hunt—the Featherweight. We cruised the prairie around Buffalo, SD, for three days during Thanksgiving week last year, occasionally getting out and walking a few coulees and smaller hills. The rut was in full swing, so there were plenty of deer. We weren't hunting for trophy bucks, just a good mature deer. At dusk the day before Thanksgiving my old compadre knocked down a 4x4.

Thanksgiving morning was chilly and foggy, and I went out with the ranch owner. We looked over a few of the fields where we had been seeing deer, but there was little to see in the fog. The fog looked to be thinning a couple of miles away near some badlands, so we headed there. As the fog diffused in the wind that was picking up, I spotted a nice buck tending a doe. We hustled toward the deer and caught up with them as they crossed the bottom of a large and rough gully. The old and familiar rifle nestled into my shoulder, and I pasted the crosshair of the scope behind the buck's foreleg at what later lased at 182 yards. It never took another step.

Yes, there are cartridges that shoot flatter and hit harder; there others that abuse the shoulder less; there are calibers better suited for certain applications; and still others that are simply fun to shoot. But if I had to choose one rifle to hunt with the remainder of my days it would have to be a .30-06. Like a longtime mate, it may not have the glitz, glamour and pizzazz of some 3,500-plus-feet-per-second magnum. It's old, grey, and its wrinkles are beginning to show. But it's solid. I know it will always come through as long as I do my part. The older I get, the more important that quality becomes.