The P85—a Ruger invention that was consistently updated—is a good example of the company's ability to improve upon classic designs. It is a dramatically revised concept of the Colt M1911, the legendary semi-automatic even inventor John Browning thought could be improved upon with the Hi Power. But Bill Ruger gave his engineering team carte blanche to create the first P-series pistol he envisioned as being evenbetter, the P85—named after the year it was designed.

Ruger's primary motivation in creating the P series was the U.S. Army's quest for a replacement for the M1911A1. He remained frustrated his Mini-14, which reached fruition in 1975, was developed too late for Vietnam. Yet, with his penchant for perfection, Ruger was not about to release a new pistol until he felt it was ready.

That turned out to be the P85, a 9 mm short-recoil pistol featuring music wire coil springs, an aluminum frame and a 4130 chrome-molybdenum alloy steel slide along with a stainless steel barrel. Featuring an ambidextrous thumb safety/decocking mechanism and a pushbutton magazine release near the rear of the trigger guard, the entire gun consisted of just 56 parts (about 20 percent fewer than the 1911A1) and weighed 32 ounces. The pistol broke down into five major components: slide, frame, barrel, recoil spring and guide rod. Both its slide and frame were investment cast, a Ruger trademark. The grips featured non-slip horizontal serrations and were molded of General Electric Xenoy high-impact plastic.

A 4.5-inch barrel and white-dot sights (with the rear sight drift-adjustable for windage) pegged this gun as a close-range defensive weapon. A non-reflective matte-black finish, lanyard ring, oversize trigger guard with recurved bow and a 15-round staggered magazine (a 10-round magazine was introduced in September 1994), made it clear the P85 was primarily intended for the law enforcement and military markets (in its 1988 brochure, Ruger referred to the P85 as, "The Police and Military Semi-automatic"). When finally introduced in 1987, it listed for an enticing $295—about $100 below its nearest competitors—which immediately made the P85 a serious contender for civilian use as well.

Although the first 10 preproduction guns were assembled in Connecticut, the next run of P85s, totaling about 220 guns, were the first Rugers manufactured in the company's new Prescott, AZ, factory. Unfortunately, by that time the Army's test trials were over and the Beretta M9 was adopted. Nonetheless, Ruger knew he now had an economical semi-automatic pistol that, in his words, "…was the best pistol of its type available."

When reports of in-the-field failures with some early Beretta M9s began trickling in, the Army had second thoughts about its decision and ordered another round of tests. Ruger promptly hired a retired veteran of the Aberdeen testing procedures and had him duplicate the entire process to make sure the new semi-automatic, with its link-activated, tilting barrel design, plus firing-block safety and hammer-decocking mechanisms, could pass the government's rigorous tests. Ruger then supplied 30 P85s to the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.

But as so many times before, politics got in the way of practicality and the tests were cancelled before any conclusions about replacing the M9 could be reached. The race was over before the P85 could even get out of the starting gate. Buoyed by his satisfaction with the performance of the P85 (which included meeting the military's requirement for a 20,000-round life expectancy), Ruger decided if the Army didn't want his handgun, there were plenty of others who would, as evidenced by a modest first-year production run of approximately 2,100 pistols. That number grew to about 85,300 by 1989.

Two of the first law enforcement agencies to adopt the new handgun were the San Diego Police Department and the Wisconsin State Patrol, setting the stage for numerous other organizations across the country and internationally as well. The P85 quickly earned an enviable reputation of being able to digest any 9 mm load—from NATO M882 FMJ cartridges to hollow points—without a hiccup. Plus, it was as rugged as an M1 Abrams tank. There are many substantiated reports of guns being dropped, kicked and even run over, yet still coming up shooting.

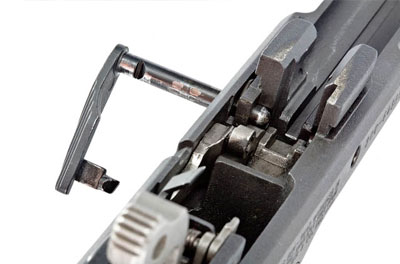

It was dropping, however, that exposed a flaw in the P85's armor. The firing-block safety could be rendered ineffective if the firing pin broke in front of the block or if the pistol was dropped on its muzzle, causing the hammer to drop and fire a chambered round. Existing P85s were recalled and the issue was quickly corrected by simply moving the blocking device from the frame to the slide. At the same time, the safety/decocking levers were slightly enlarged to make them easier to engage. The result was the P85 MKII (Ruger still offers this free retrofitting on any P85; retrofitted guns are stamped "MKIIR" near the safety).

There is another, more esoteric flaw with the P85. When discussing it, the phrase "good ergonomics" rarely enters into the conversation. Visually and physically, the handgun is clunky and lacks the svelte look and natural pointability of semi-automatic pistols that more closely follow the 1911's profile. Moreover, its bulk and sharp angles are not conducive to concealed carry. Plus, the extremely long and somewhat gritty double-action trigger pull doesn't aid accuracy, which hovers around 3 inches at 25 yards. Yet, in its defense, manually cocking the hammer and firing the pistol single action for the first shot is a practical solution (even though the P85 cannot be safely carried cocked and locked). And it can be argued a 3-inch group at 25 yards is all one really needs in a self-defense pistol.

The P85 was discontinued in 1990 (with a stainless steel version made that year only). Two years later, the P85 MKII was replaced by an upgraded P89—in blued or stainless steel versions. That was followed by the P90, which was chambered for .45 ACP and came with a single-stack, seven-round magazine. Next came the P91 in .40 S&W, and a more compact, 4-inch-barreled P93 in 9 mm. A slightly larger 9 mm and .40 S&W version, the P94, was offered in 1994. The P95 ushered in a new world of polymer-frame pistols for the P series, and resulted in a contract from the U.S. Army tank command. Ruger then came out with a polymer-frame P97, chambered in .45 ACP and available in either a double-action-only model or a striker-fired version. The P97 was discontinued in 2004, with the P89 continuing on until 2007 and a KP89 stainless version lasting until 2009.

In all its variations there were more than two million P-series Rugers made in just a little more than two decades—not a bad run for what started out as the P85, a handgun that ushered in a new era for one of America's most innovative firearm manufacturers.